Sunscald

This occurs when tomato plants have lost a lot of leaves and the tomatoes are exposed to the direct rays of the hot sun. (This is common on pepper plants as well – as they are in the same family as tomatoes.) Usually sunscald takes place on plants that were previously shaded or leafy but suddenly were exposed to the sun.

If for some reason your tomato plant is suddenly exposed to the sun, drape a lightweight material over the fruit during the brightest part of the day to minimize exposure. Try to keep leaf diseases at bay as much as possible – though sometimes stuff happens, as we all know. Seek out tomatoes that are resistant to Septoria leaf spot and early blight. (But then again, if your tomato catches early blight, it’s pretty much hosed – and sunscald will be the least of your worries as your tomato plant is pretty much doomed.

A nice dose of nitrogen once the fruits have set will help guard against sunscald.

Pick sunscalded fruits if they’re close to getting ripe and let them ripen inside. The sunscalded part is fine – just cut it off before you eat the tomato. Don’t let black mold start on the sunscalded part, or then the tomato will go bad.

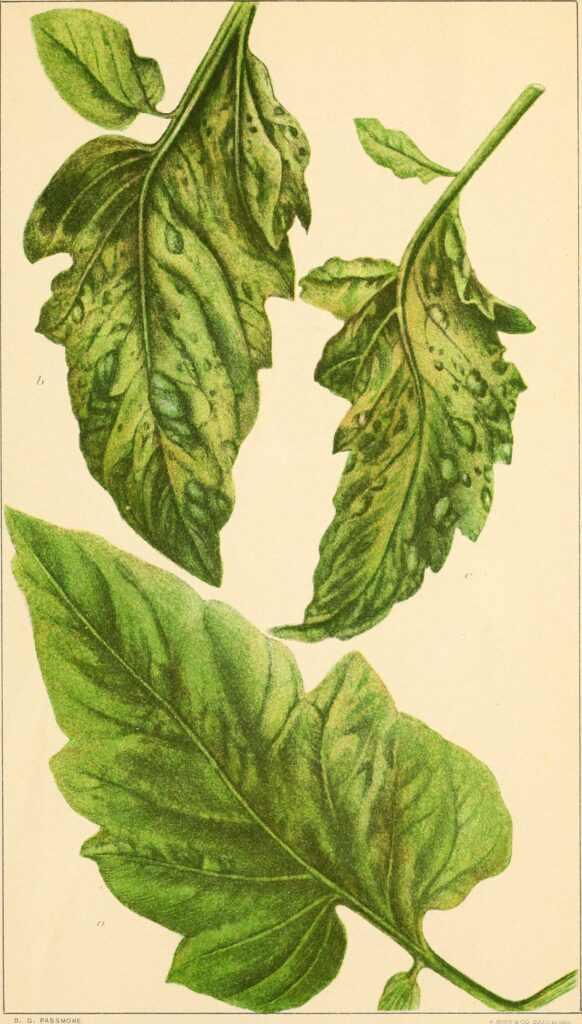

Tobacco Mosaic

If your plants had tobacco mosaic, burning or composting the leaves will not kill the virus, because the viruses can survive incredible temperatures. That is why you shouldn’t crush out a cigarette in your garden.

If a tobacco plant infected with the virus got into that cigarette, its ashes will pass the virus on to your roses and other plants, especially plants in the nightshade family, such as potatoes and tomatoes. So don’t smoke in the garden, or at least don’t tap out your cigarette ashes in the garden, and don’t put cigarettes in the compost or your soil.

If a tomato plant develops the crazed leaves of tobacco mosaic virus, pull it up and throw it out of the garden. Don’t compost it – just throw it away. Don’t plant any member of the Solanaceae family there – no eggplants, tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, or Nicotiana flowers – as the disease will affect any member of this family.

Blossom End Rot

This might be a problem on tomatoes (and also peppers) if the soil moisture has been uneven. This disease will also come back year after year. It is due to a lack of calcium in the soil, and shows up as a black spot on the blossom end that grows bigger and blacker and uglier – the black spot is from a fungus that attacks the weakened fruit.

The kicker is that it’s possible to have a lot of calcium in the soil, but an alkaline soil (pH of 8 and up) can “tie up” the calcium – that is, the high alkalinity of the soil creates a tighter bond between the soil particle and the calcium, and so the plant root is unable to pick that calcium off or take it for itself.

TL;DR – If blossom end rot is a recurring problem, get a soil testing kit from your local University Extension service and find out what is wrong with your soil. Do this in fall, or even in summer. That way, you’ll have plenty of time to find out what your soil needs, and then you can keep blending in the proper amendments, keep adding compost, keep adding good organic mulch. You’ll also be shown how to maintain the soil’s pH to a more favorable level. Maybe by spring your soil will be in better shape and ready to release calcium (and every other nutrient) like crazy.

Another difficulty is when you get a lot of drought, then a lot of heavy rainfall. This is why it’s so helpful to water your plant consistently every week (if needed) or even twice a week if it’s especially dry. Keeping the soil evenly moist helps keep the disease at bay.

When you notice blossom-end rot starting on your tomatoes, however, you do have some short-term fixes available. You can actually water several antacid tablets into the soil around your tomato plants, which will make calcium readily available. Or give your tomatoes a foliar feeding of any fertilizer that has calcium as one of the minerals. Water the leaves and roots for best results.

Tomato with late blight.

Late Blight and Early Blight

Last year my Celebrity tomatoes developed dark blotches when the tomatoes were still very small and green. Each time the blotches quickly spread over the whole fruit and turned it into brown mush. I was aggravated. I had one tomato that I thought had finally made it to maturity, but when I picked it up, I found it had been half-eaten by this rot.

This wasn’t limited to the tomatoes touching the ground, either; tomatoes up in the air were also getting these blotches. And, even stranger, the tomatoes on the other side of the garden were doing just fine – no weird blotches. What was going on?!

My tomato had late blight, the same disease that caused the great potato famine in Ireland. (Potatoes and tomatoes are in the same plant family, the Solanaceae, which means they share many diseases.) It develops in wet, humid, cool conditions – the kind of weather that my tomato plants had been experiencing. When you have a blighted tomato, one side of the fruit may look lovely, but the other side is slimy, rotted away, and brownish-black.

Late blight (also known as potato blight) is caused by Phytophthora infestans, an oomycete (a fungus-like microorganism). There are many different varieties and forms of blight, including anthracnose fruit rot (which makes bulls-eye shaped circles on tomatoes), early blight (where the petal ends on the tomatoes turn white with fungus), and Septoria leaf spot (which affects only leaves and stems, leaving them peppered with little black spots).

The leaves on plants affected by blight have little brown spots on them, as if a few drops of acid fell on them. On the back of the leaves, or on their tops, is a lot of white, powdery mold.

It should be noted that in some places, the fungus has developed resistance to systemic fungicides. However, external fungicides – those that repel fungus by changing the pH of the outside of the plant – still do the trick if you start spraying them immediately after you plant your tomatoes and potatoes. Keep spraying the fungicide weekly (or as often as the label specifies).

The drawback is that the fungicide will have to be reapplied every time it rains. Also, by the time blight has appeared on your tomatoes, it will be too late for a fungicide to do any good. Fungicide can be used only as a preventative measure, not a cure.

However, some experts are not sure how much good spraying actually does, so you might take notes about your spraying program. See what works and what doesn’t.

One way of outsmarting the disease may be to plant a wide variety of disease-resistant tomato plants, not just one variety. Even if you lose one or two tomato plant to the disease, the other varieties could resist it. Also, space the tomato plants well apart from each other. My tomato plants were scattered around the garden, well apart from each other, and this probably saved some of my plants.

Mulch the potatoes and tomatoes to avoid water splash-up from the soil. Sometimes blight spores are splashed up onto the plant from the bare soil. Also, water early in the day so the plant has time to dry off before nightfall. Don’t plant tomatoes where you had any potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, or peppers the previous year. This can be tough if you have a small garden and not much room to move things around. Do your best.

Give potato and tomato plants plenty of space in the garden for good air circulation. You might trim off parts of your tomato plant, especially if it’s a monster plant, to let the air travel through.

As soon as you see infected fruits or foliage, remove them and burn them. (Don’t compost them unless your pile gets really, really hot.) Bag them up and get them out of the garden so no more fungus spores can spread. (Spores come out of the fruiting bodies in the brown spots.)

Some tomato plants, such as Mountain Fresh, Mountain Supreme, and Plum Dandy, show resistance to the disease. Look specifically for these kinds of tomatoes if you’ve had blight in the past.

When you fertilize, keep the nitrogen levels low. Nitrogen makes leaves juicier and more succulent for diseases. Don’t save seeds from infected crops, since the disease can be spread through the seeds.

If blight gets out of control, you’ll have to pull up and destroy any infected plants as soon as you see them. Keep spraying fungicide on the survivors.

If you had trouble with late blight in your garden last year, take preventative measures by spraying those vegetables with Bordeaux mixture every two weeks during hot and humid weather. Copper fungicides will also work against this disease. It helps if you pick off the affected leaves, too, and dispose of them away from the garden (not in the compost heap!). Don’t allow volunteer potatoes or tomatoes to grow in your garden.

Fusarium Wilt

Fusarium wilt is a fungus that attacks tomato plants, as well as squash and melon plants. Fusarium starts in the roots and moves from there into the stems. If your plant is hardly growing and is all stunted, that’s probably what the problem is. Then they wilt and die. Sometimes a white fungus starts growing on the dead vines.

If this happens, get the dead vines out of the garden ASAP so the spores don’t spread back into the garden. Don’t plant any melons or tomatoes there next year, or the next, because Fusarium will linger in the soil. Your best bet is to plant resistant varieties.

Heat Will Stop Tomato Production

When the heat is particularly intense, plants will stop producing. Tomatoes stop production when temperatures soar above 90 degrees. Cucurbits (zucchini, cucumbers, and muskmelon) might produce a bunch of male flowers but no female flowers, much to the gardener’s frustration. (Unless she has more than enough zucchini.)

Temperatures of 85 to 90 degrees in the day and night temperatures above 75 degrees will also stop tomato flowers from being pollinated, and even cause them to drop off the plant.

Tomatoes on the vine and already close to being ripe will be okay in the heat – but only up to a point. These fruits will be more susceptible to sunscald.

Tomatoes will have a hard time reaching full ripeness in the heat. Fruits that typically ripen as red will turn orange and then be unable to finish ripening. Pick these fruits and bring them inside, out of the sun, so they can finish ripening. This will help ease the energy burden on your tomato plant, too.

However, some heat-tolerant tomatoes will keep producing even in high temperatures. Heatmaster, Solar Fire, Summer Set, Florida 91, Phoenix, and other “heat-set” tomatoes have been bred to bear fruit even when the temperatures soar. Or, you can plant determinate tomatoes, which will bear their fruit and then be all done before the serious heat starts up.

Another alternative is to set up shade cloth to keep the sun off the tomato plants. Set the shade cloth up so the tomatoes will get a good dose of morning sun, and then are shaded from the hot afternoon rays. Use “50 percent” shade cloth, which will reduce sunlight by 50 percent and heat by 25 percent. Then join the tomatoes in the shade with a good book.

Be sure to have a nice, thick layer of mulch over the tomato roots. This will cool the ground and help keep the plant cool. Also, keep watering the plants to help with heat stress.

Keep an eye on diseases. Heat-stressed plants tend to be more susceptible to diseases and insects. So, if you see something coming on, then nip it in the bud.

From IF YOU’RE A TOMATO I’LL KETCHUP WITH YOU: Tomato Gardening Tips and Tricks