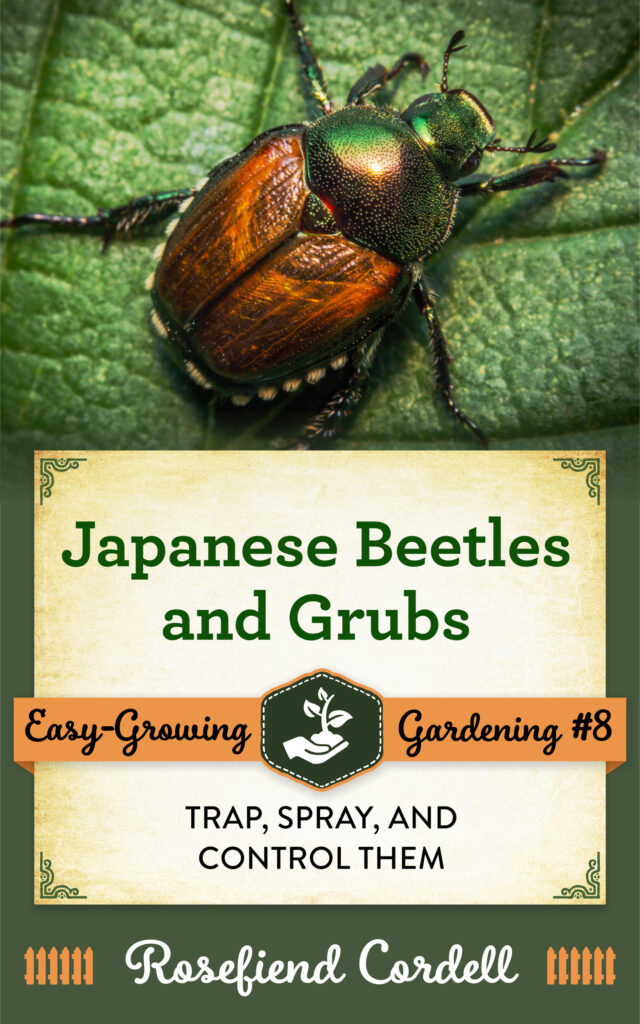

Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica) are about the size of a dime, about a 1/2 to 3/4 inch long. They sport an iridescent copper shell with a green head, with six tufts of white hair along their sides under the edges of their wing shells. They’re actually quite a pretty insect when they aren’t attacking your roses and apples en masse.

History

In August 1916, two inspectors from the New Jersey Department of Agriculture were at the Henry A. Dreer nursery near Riverton, N.J., inspecting plants for unknown diseases or insects (as they do). They collected a dozen unknown beetles on that visit, so they checked the insect collections at the National Museum in Washington, D.C. There they found that the specimens were Japanese beetles. At this time, the beetles occurred only on the main islands of Japan – Honsu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and Hokkaido.

It’s not known for sure how the beetles arrived on American soil – they’re thought to have arrived in a shipment of Iris kaempferi (known now as Iris ensata), a popular garden plant at that time. (The Japanese iris is still a nice, low-maintenance perennial.)

In Japan, the beetle was not a garden pest. The main islands at the time were heavily forested mountainous country, conditions that didn’t allow the beetle to do very well. Furthermore, due to the cool weather in the Japanese islands that the beetle lived in, the beetle had a two-year life cycle, so it didn’t reproduce rapidly. Habitat for the beetle’s larvae (the grubs) was also scarce in Japan. The nation does have grasslands on Hokkaido, but they also contain a host of natural predators that keep the beetle numbers down.

However, when the beetle showed up in America, those checks and balances didn’t exist.

Warm weather that allows it to move through a complete life cycle in one year –

No natural enemies to keep it in check –

A ton of habitat for its grubs, in the form of everlasting lawns –

300 species of plants serving as a veritable all-you-can-eat buffet –

This country is a veritable paradise for that beetle.

The Japanese beetle hit America and flourished. In very little time, the beetle spread through the East and clear out to the Mississippi.

Entomologists had already recognized its destructive potential and had jumped into action. The year after it was discovered, in 1917, the Japanese Beetle Laboratory was established in New Jersey to study these insects and try to slow its spread.

A note on Japanese Beetle habits

A good tactician understands that, when you have the resources for it, a war should be fought on more than one front. Each front should target your enemy’s weak spots. You just keep hitting and moving, hitting and moving, until you have won the battle or have routed your enemy. And always stay one step ahead of your enemy.

These tactics, though greatly simplified, also apply to fighting diseases and pests in the garden and in the field. With Japanese beetles, several different methods of control are necessary for the most effective knock-down of these noxious pests.

These tactics include understanding the habits and life cycle of the Japanese beetle.

Knowing what an insect needs to live is key to good control. Then you can target all of these things to kill off a large infestation.

Habits and lifecycle

A Japanese beetle’s life usually starts on some hot July night, when a female Japanese beetle that has been chomping up apples and leaves and rose blossoms flies down to the grass, works her way down through the grass to the soil. There she will dig a little burrow two or three inches deep and lay a little cluster of eggs. The next morning, she crawls to the surface to fly back up into the trees, find another mate, and eat a thousand more leaves, and the next night she’ll lay more eggs in a little burrow.

These eggs will eventually turn into approximately five million grubs … actually, that’s not true. Each female lays about 40 to 60 eggs – still more than enough. There’s nothing I hate more than an overachieving beetle.

The Japanese beetles themselves die off by the middle of August, but the eggs are still there, as are the grubs, busily hatching and growing underground.

The eggs absorb water in order to grow, then hatch in midsummer, about mid-July. The grubs, or larvae, emerge an inch or two underground, where they begin to feed on grass roots. These white grubs are an inch long when fully grown and rest in a C shape. When you turn over the soil in your garden, you’ll probably find a couple of grubs there in your shovelful of dirt, though some of those grubs might also be for June bugs, chafers, or some other grub from the Scarab family of beetles.

It’s harder to tell Japanese beetle grubs from those of June bugs and other related beetles, because the grubs are generally differentiated by the pattern of hairs on their hind ends. Entomology is fun! No, seriously, it really is.

During summer, when the ground is warm, the grubs inhabit the top two inches of the ground, feeding on grass roots. By September, these grubs are almost an inch long. In late fall, the cold weather will drive the grubs deeper into the soil. They’ll dig about four to eight inches down and hibernate there through the winter, safe from the worst of the cold.

In spring, the grubs return to the grass roots to feed until they’re plump. In late spring, the grubs pupate, metamorphose into beetles, and pop up out of the soil for their late-spring and early-summer buffet of destruction. And, of course, mating. I was going to say “mating like rabbits,” but rabbits ain’t got nothing on these little hedonists.

It’s important to note that newly-laid Japanese beetle eggs and newly-hatched grubs need enough rain to keep from drying out. Years with bad droughts can put a dent in the grub population by destroying the eggs, because the eggs must absorb water in order to allow the embryo beetle to develop.

If your lawn is having trouble with grubs, and if you’re able to do this, stop watering your lawn from June to mid-July, in order to help kill off Japanese beetle eggs. This is probably a good reason to grow drought-tolerant turfgrasses in your lawn.

The grubs themselves are more resistant to dry soil. The grubs usually go through three instars (that is, growing periods that end with a molt of their skin as they grow too big for it); during each instar, the grub can withstand a huge loss of water in its body. During the first instar, right after they hatch, these grubs can lose up to 44 percent water before they croak.

If the soil temperature drops to -9.4 degrees Celsius, or 15 degrees Fahrenheit, nearly 100 percent of the grubs will die. But this has got to be the soil temperature, not just the air temperature. This drop of soil temperature can be brought on by sudden, extreme changes in the air temperature, and no snow cover. (A blanket of snow insulates the soil against these drastic, grub-killing drops – too bad.)

Also, freezing rain causes the water in the soil to freeze, stabbing many grubs with ice crystals. So there is that.

A very dry summer or a terrible freezing winter causes a drop in the local population, but adequate rainfall and favorable temperatures can cause a spike in the numbers of beetles the next year.

An additional note: Beetles are very alkaline creatures, but they have a very broad tolerance to soil pH, so acidic soils don’t seem to bother the grubs at all. Also too bad.

What attracts Japanese beetles?

The answer to this is straightforward: food and sex.

Japanese beetles find food by following certain chemical odors in the air. They find love, or whatever, through following pheromones in the air. And the more pheromones there are in the air, the more beetles there are in an area, all of which are going at it. Beetles will fly long distances to find these party trees, as you’ve probably noticed when you go outside and find your apple tree dripping with mating beetles.

Love is in the air

Male beetles will fly to plants where females were feeding, or pretty much anyplace where the females are. In the morning, when the females climb out of the holes they’ve dug to lay their eggs, a bunch of males will fly over and land and try to mate with her. And she’s like, “Dudes, I just woke up, geez.” An entomologist noted that males always approached a female against the wind, and when the wind shifted, they would change their path to follow the trail of pheromones coming off her.

So if a couple of beetles are on a plant, you can bet they’ll soon be joined by six hundred more.

Note: this is a good reason to start killing the beetles as soon as they start showing up. If you can bring their numbers down right at the start, they will have a harder time infesting the plants in your yard.

An old study found that 50 percent more beetles landed on infested foliage than on uninfested foliage. This is why beetles will flock to one plant, while a plant of the same species in the same area will be relatively clean of beetles.

Image by Jan Haerer from Pixabay

The smell of food is also in the air

Certain essential oils, some fruit fragrances, and the smell of fermentation will attract the beetles. The beetles are always attracted to fruits with high sugar content.

Japanese beetles are also attracted by the smell of fermenting fruit on the ground or in the trees. Some entomologists recommend removing rotted fruit to protect the sound fruit from beetle attack.

Beetles gather in huge numbers on early apples and peaches, forming clusters in the shape of a ball, feeding until all that remains is a core or a pit. In 1940, two entomologists counted 296 beetles on one apple. The beetles also cluster in balls occasionally on foliage or blossoms.

On fruit trees, the beetles prefer fruit that’s been damaged or has been infected by disease over healthy fruit. This is because it’s easier for the beetles to eat their way into an apple if there’s a hole in the skin, or into a peach if there’s a spot of rot.

The same goes for grapes. The beetles ate grapes that were infested with grape berry moth, or those that were infected by black rot – even if the grapes were immature. Only when that food source was exhausted did the beetles move on to healthy grapes nearby.

So remember: To discourage Japanese beetles, get rid of rotting fruit, diseased fruit, or fruit with holes in it.

Japanese also attack and defoliate unhealthy trees first before moving on to healthy trees. One study noted that peach trees that were infected with the peach yellow disease and little peach disease were attacked by the beetle, while healthy trees nearby were mostly unscathed.

So be sure to keep your trees healthy. Mulch them with a layer of compost and water it in. Keep the weeds down around the tree so there’s less competition between roots.

Beetles never stay long in one place, and constantly move from one plant to another. They can fly several miles in a day. One reason why beetle control is so difficult is their extreme mobility. When you kill off beetles, more beetles move in from elsewhere.

The adults feed on over 300 plant species (lately I’ve seen that number quoted as being 400). They chew out the tissue between the leaf veins, leaving lacy skeletons that fall from the tree. So if you see a lot of lacy leaf skeletons collecting on the ground in May or June, look up – you might see the beetles in the top branches of the tree. Beetles will start in the top foliage of trees and plants, in places that are exposed to full sun, and then work their way downward through the plants.

Note: Beetles don’t like to feed in the shade, so if you have a shade garden, you’re not going to see as much beetle damage.

The most feeding takes place on warm summer days when the sun is out, when the temperatures are between 83 and 95 degrees. If the relative humidity falls below 60 percent, beetles don’t want to fly, so they stay in place and feed a lot instead. They also do not fly on cool, windy days, and they don’t fly on rainy days.

FROM JAPANESE BEETLES AND GRUBS: Trap, Spray, and Control Them