When I was a budding horticulturist (yes, that pun was intentional, sorry), I occasionally drew landscape designs for a small installation company. Generally I worked out in the field, moving river rock in the hot sun or pulling weeds in various gardens where the homeowners never spoke to me but their kids did. But sometimes when the boss had too much going on, he’d pass the design work on to me.

“These people want yews around the foundation,” he said, or, “They want junipers and pampas grass,” or, “They want Alberta spruces, one on each side of the door.” Just the usual old landscaping clichés, over and over.

I asked the boss, “Man, why do we keep giving people the same old things?”

He shrugged. “It’s just what people want.”

“What if you introduced them to some cool new ideas?” I asked.

He just laughed and sent me off to draw up a little design with creeping junipers and Alberta spruces (I always swapped those out with something else because Alberta spruces are terrible landscape plants in Missouri).

But one day, a client called, and she wanted a perennial garden. Oh my gosh, at last something good! I was in heaven, especially since I did my whole senior thesis about English gardens. The wonderful thing was that she was interested in plants, so my boss sent me to talk to her instead of talking to her himself.

So I talked to the lady, and she showed me around the little landscape she had, which included a little vegetable garden in one sunny corner of the yard.

“Have you ever thought about incorporating some of the vegetables and herbs into the landscape itself?” I asked. “You have this small yard, so you don’t have a lot of space to work with. Why not make a landscape that’s functional and pretty?” This had been something I’d thought about occasionally, but I hadn’t tried it before because all the gardening books seemed to indicate that vegetables and ornamentals should be kept separate, and never the twain shall meet.

She liked that (she was a pretty cool lady), so I worked various herbs in with the other flowers, tucked a rhubarb plant in one corner, tried out some Swiss chard in the front of one of the beds. Of course, I made mistakes along the way. Chives really like to reseed and spread like crazy, and I had to fight with them when they tried taking over the primroses. The chard got a lot bigger than what I expected, but she fixed that issue by eating the chard and sending some home with me, so that worked out very well. Red-veined sorrel made a dependable eye-catching spot of color in various places in the landscape. Burgundy lettuces made a cute edging until they bolted, and then they had to be taken out and replaced with other plants. A sage plant I’d included got bigger and more scraggly than I expected, but I always liked having it there, just to rub the leaves and smell it when I walked by.

They were small things, but small details make up the whole picture.

It seems a shame to relegate food plants to second place in the garden. They aren’t as tidy as ornamentals, but they were bred to produce bountiful crops, but they can also look very good, and many of them can fit in well in a mixed border.

A year or two went by, and then I started working as a city horticulturist. Looking back, I wish I had remembered that little episode in planting city gardens. I could have planted apple and chestnut trees in the parks system. I’m sure my new boss wouldn’t have gone for that, and to be honest, I was stuck on the idea that municipal gardens weren’t meant for food planting but for aesthetics.

Now I regret that, as unemployment is skyrocketing, in these days when a full-time minimum-wage job no longer will pay for a roof over your head. Man, if I’d planted apple, pear, and chestnut trees in Krug Park and Hyde Park and along the parkway, that would have helped people who are in dire straits now. I could have created some actual food forests that would be, right now, benefiting some of our taxpayers in a very real way.

At any rate, if you’re able to set up a garden in your yard, even a small one, you’ll generally get a return on your investment. Of course, making a small garden today doesn’t mean you’ll be able to live completely off the grid tomorrow. Complete self-sufficiency is a whole ‘nother level of work. All the same, there’s a contingent of anti-gardening people on social media, swear to God, and they’re all like “You can’t live on your own gardens, millions have died of famine, you shouldn’t encourage people to grow gardens because what happens if they fail? It’s too cruel to dash their hopes and dreams like this.” Yes, people online actually say this.

Sure, not every enterprise succeeds, but geez, that’s life; and I’m not going to tell people to give up before they even try. That’s like saying, “You shouldn’t try to learn how to play piano because you’re only setting yourself up for heartache and disappointment.” I don’t know about these people; to me, it’s like telling you something that took place in the Twilight Zone.

(However, if you truly want to aspire to self-sufficiency, get a copy of The Encyclopedia of Country Living by Carla Emery, which is a good overview of what true self-sufficiency entails.)

Growing your own food gives you a measure of independence. It’s great to go to the local farmer’s market and get fresh foods that taste great, but it’s even better to save the seeds and grow your own. (Protip: If you find something you especially like at the farmer’s market, they’ll probably tell you what kind of tomato or bean you’re buying – and if it’s an heirloom variety, you can save back the seeds and add them to your garden next year. Then you can go to the farmer’s market again and try more new and old varieties. It’s the ultimate “taste and try before you buy” emporium.)

By buying local and growing your own, you’re supporting people, not corporations, and getting the freshest and best food in your own backyard. Also you know it’s organic, so it’s healthier than the tomatoes you buy at the store, which are sprayed with who knows what, picked when they’re green and rubbery, transported hundreds of miles, and made to artificially ripen before they’re tossed onto a produce shelf. (Further note: Store-bought tomatoes are not bred for taste, but for being able to be transported hundreds of mile and handled by countless people and machines without bruising. Yum!!)

Including vegetables, edible flowers, and herbs in your landscape is an excellent way to get good food, make the most of your yard’s space, add some new elements to your landscape design, and (if you live in one of those stalkerish Homeowner’s Associations that won’t allow you to grow vegetables in your own yard) a way to fly under the radar so you can have tomatoes without getting fined to death.

Trying something new is always fun. Foodscaping — permaculture — building an edible landscape is one way to break out of the gardening doldrums.

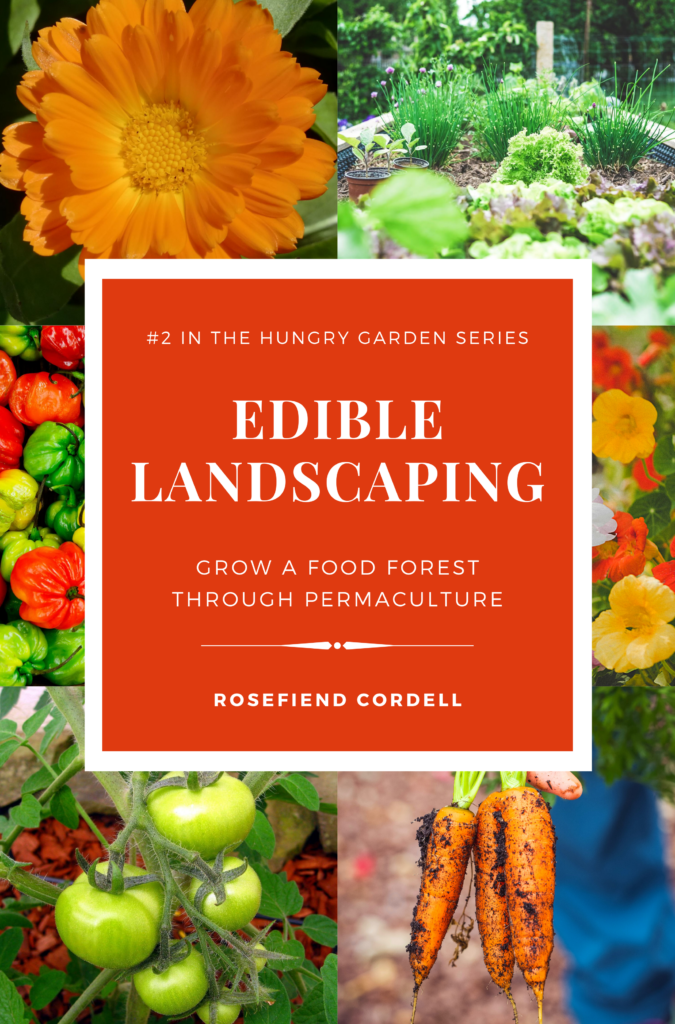

FROM my forthcoming book Edible Landscaping: Foodscaping and Permaculture for Urban Gardeners (The Hungry Garden Book 2).

Preorder today! (The Amazon page says it’s due out on October 1, but I am going to try to move this up because I think I can get this finished sooner.)